The wealth of abolitionist activity that took place in St. Catharines during the Underground Railroad Era tells a story of a community of people committed to aiding in the escape of Freedom Seekers. The area attracted many well-known abolitionists in the Underground Railroad era. Harriet Tubman and Hiram Wilson, both called St. Catharines home for a time, William Still corresponded with many members of our Freedom Seeking community and John Brown visited on his trip to Canada. These figures and the countless others that aided in the movement sought to aid in the creation of a home for Freedom Seekers. These figures did more than just facilitate the removal of Freedom Seekers from dangerous places, they helped facilitate a community. Their commitment to change was what continuously brought people into their community.

In Benjamin Drew’s book the North-Side view of Slavery his interview with John Stewart of St. Catharines provided an insightful look into the impact of how abolitionists treated Freedom Seekers. Stewart describes his coming among the abolitionists when he says, “After I got among the abolitionists, I was almost scared; they used me so well, I was afraid of a trick. I had been used so ill before, that I did not know what to make of it to be used so decently.”[1] It is difficult for us to imagine a world where someone being nice is cause for concern. Or for us to imagine a world where cruelty is the only experience you have ever known. That Freedom Seekers were anxious about their treatment in Canada provides understanding on why the abolitionist community was required beyond arrival in St. Catharines. Finding freedom often came at the cost of being separated from family, friends, and culture and suddenly finding oneself in a new home as a refugee. Abolitionists played an important role not only in fulfilling the immediate needs of entering a new society but also the long term needs of a community.

The details included within William Still’s book; The Underground Railroad contains correspondence written by or on behalf of the Freedom Seeker. Letters written reassure those that have helped them along the way, that they have made it to St. Catharines safely, to express their views on what it is like to have freedom and to express their thanks. One letter written by St. Catharines Freedom Seeker, Solomon Brown, in 1854 says, “It is with great pleasure that I have to inform you, that I have arrived safe in a land of freedom. Thanks to the kind friends that helped me here.”[2] These friends would have been the abolitionists and previously-settled refugees that helped in the transition to freedom. The word “friend” does not seem quite powerful enough for the bond that existed because of experiencing this journey together. The import of writing to ensure that Still and the other members of the Underground Railroad knew that they were both well and appreciative provides insight into the impact of these individuals. That these refugees felt it necessary to write as one of their first acts in Canada indicates the value placed on these relationships. The community that formed around the Underground Railroad forged ties that spanned the international border and continued as Freedom Seekers transitioned from the Underground Railroad into their new life. This bond was strong enough that upon entering the community in St. Catharines many Freedom Seekers turned to abolitionist activities themselves and provided what they could to ensure their community grew.

In the Freedman Inquiry Commission testimony of John Kinney, Kinney details the existence of three societies in St. Catharines that provided aid the community of Freedom Seekers. Kinney tells us that there was a Women’s’ Society who generated the necessary funds to aid those who needed medical care or burial. He details that the Masons were happy to take care of fellow Masons and there was a community-based society where the membership put in funds at every meeting. This money was used to cover the costs of living when there was a case of illness in the community.[3] Community aid work is not something that most would associate with abolitionist work, however, this work was desperately needed in St. Catharines. This community was where members understood the realities of what slavery meant and did everything they could ensure that the newest arrivals of Freedom Seekers could be successful. Success was not always a guarantee in a society that held prejudice against these refugees from the moment that they arrived.

The worldview of the Underground Railroad era is much different from the one we experience today. The industry of these societies in coming together helped to ensure that these new immigrants had a safety net. This is what allowed many to build a life in St. Catharines. In the North Side View of Slavery, an interview with William Johnson of St. Catharines details his escape to Canada in which he received frost bite in two of his toes. Due to this injury, he states that he had been unable to work and had found, “good friends in Canada.”[4] While not explicitly stated it is likely that these good friends would have been the type of community abolitionists that we are discussing and that some of the aid societies in the community would have been the ones providing funds Johnson needed to live while he recuperated. Johnson shared that he was taking the time while recuperating to also learn how to read. He shared that he knew many Freedom Seekers who were taking the opportunity to learn how to read.[5]

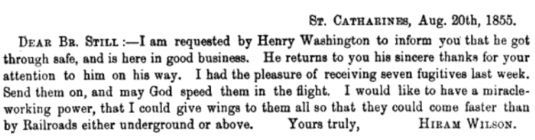

The education of Freedom Seekers was the objective of a particularly well know abolitionist, Reverend Hiram Wilson. Wilson made his way to St. Catharines after having travelled around Canada West working for the movement. Named a delegate for the World Anti-Slave Convention of 1843, Hiram was an active participant in the freedom movement[6]. His contribution centred around the establishment of schools for the education of the Freedom Seeker. In the years prior to coming to St. Catharines he had set up ten schools around Canada West. With the passing of The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 Hiram relocated to St. Catharines and opened a school while also providing aid to Freedom Seekers when they reached St. Catharines. Still’s book has letters written to him by Wilson keeping him appraised of the arrivals of the refugees that Still had sent. Wilson wrote one such letter to Still on August 20th, 1855, it read: “Dear Brother Still: – “I had the pleasure of receiving seven fugitives last week. Send them on, and may God speed them in the flight. I would like to have a miracle working power, that I could give wings to them all so that they could come faster than by railroads either underground or above.”[7]

Hiram’s letter speaks to the strength of the movement in St. Catharines and the movement in general. This community was brought together for the aim of carrying out justice. It ran the length of the Underground Railroad and the wider world of the British Empire. The relationships forged on the road to freedom provided Freedom Seekers with comfort as they turned their attentions to forging a new life for themselves. It was this community that provided them the helping hand they needed and in turn, turned the Freedom Seekers into abolitionists themselves.

Watch for part three of the series on the daily lives of Freedom Seekers on February 20. In part three, Abbey will discuss, letters to the United States written by Freedom Seekers. Catch all four parts of this series from Black History Month 2022 using the tag or category ‘Black History’.

Abbey Stansfield is a Public Programmer at the St. Catharines Museum and Welland Canals Centre.

Works Cited

[1] Drew, Benjamin. A North-side View of Slavery: The Refugee: Or, The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada. United Kingdom: J.P. Jewett, 1856 (41).

[2] Still, William. The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom, as Related by Themselves and Others, Or Witnessed by the Author; Together with Sketches of Some of the Largest Stockholders, and Most Liberal Aiders and Advisers, of the Road. United States: People’s Publishing Company, 1871.

[3] Transcripts of American Freedman’s Inquiry Commission Testimonies, 1863. Interview with John Kinney.

[4] Drew, Benjamin. A North-side View of Slavery: The Refugee: Or, The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada. United Kingdom: J.P. Jewett, 1856 (30).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Hiram Wilson. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www2.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/LaneDebates/RebelBios/HiramWilson.html.

[7] Still, William, and William Gilliam. “William Gilliam.” Letter. In The Underground Rail Road: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, & c., 261. Philadelphia, PA: People’s Publishing Company, 1871.

Informative, well written and most enjoyable-good work!!